Watsonville Community Hospital’s director of pharmacy, Jennifer Gavin, addresses Thursday’s International Overdose Awareness Day. Credit: Kevin Painchaud / Lookout Santa Cruz

In March 2020, Gilroy resident Lisa Marquez woke up to police officers banging on her door. They told her that her 17-year-old son was in an ambulance on the way to the hospital. By the time she got there, he had died of fentanyl poisoning after ingesting what he thought was Xanax from a local dealer. Shortly afterward, Marquez took to Facebook to warn others about the risk of fentanyl poisoning. Her post got nearly 3,000 shares.

“From that day on, I’ve been sharing the story to anybody who wants to listen,” she tearfully told the crowd of nearly 100 community members and service providers who gathered at Watsonville Community Hospital on Thursday afternoon to mark International Overdose Awareness Day. “I share my story because it can happen to anybody. And because I don’t want to meet another mom in my position because it’s the worst pain ever.”

Aiden Fuller, 17, is far too familiar with the story. He had been clean for about a year before last week, when he relapsed. Still recovering, Fuller said it was difficult to make it to the event, but he felt that he had to.

“I just had to pick myself up and come here to stand up for my recovery,” he said. “That’s really what matters.”

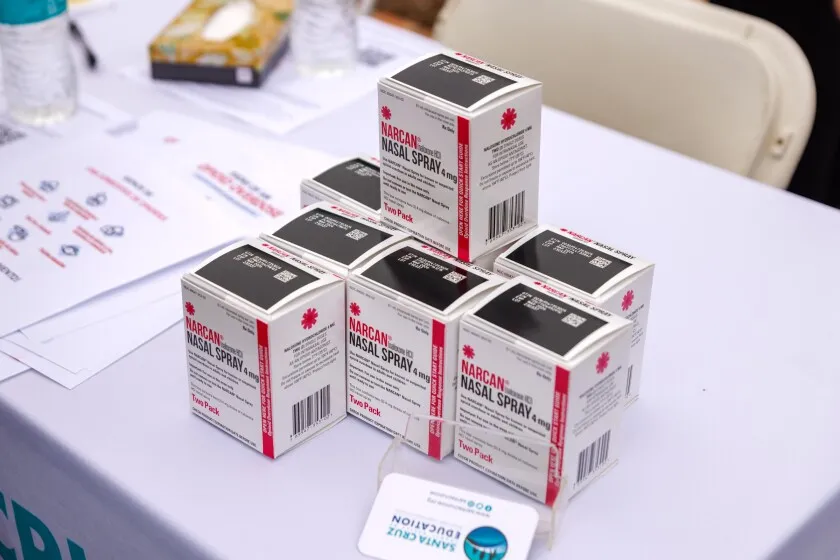

The purpose of the event was to discuss the acute opioid crisis, learn about substance-use programs and resources, and hear from community leaders and those directly affected by the crisis. Organizers also provided free Narcan, the potentially life-saving overdose-reversal medicine.

That very well might come in handy. County Deputy Health Officer Dr. David Ghilarducci told the crowd that in 2022, paramedics used 1,500 milligrams of Narcan compared to just 200 milligrams only five years ago in 2017. One dose of Narcan is 4 milligrams.

“That just shows you the rapid rise that we’re seeing,” he said. “We’re seeing stronger drugs and more people using them. This is truly a crisis of epidemic proportions.”

Lisa Marquez next to a picture of her son, Fernando, who died of fentanyl poisoning in 2020. Credit: Kevin Painchaud / Lookout Santa Cruz

Twenty-one harm-reduction and substance-use support organizations from around the county — including SafeRx, Janus of Santa Cruz County and The Camp Recovery Center — attended the event’s resource fair to give out their information.

Started in 2001 in Melbourne, Australia, by Sally J. Finn of the Salvation Army, International Overdose Awareness Day is the world’s largest campaign to end overdose, acknowledge the pain of lost friends and family and break down the stigma surrounding addiction.

Marquez, who had come from another International Overdose Awareness Day event in San Jose, told Lookout that she felt some relief seeing and hearing about all of the services in Santa Cruz County.

“I hadn’t heard of most of this, so it makes me feel a little bit better,” she said, adding that she doesn’t know of many accessible services in Gilroy, either. “I could maybe direct some parents who feel hopeless.”

But even with the many services in Santa Cruz County, those working within the organizations point to limited space in recovery and treatment centers as well as a lack of youth-centric services as big issues in combating the opioid crisis locally. Maisy Morrison, director of strategy and design for substance-use disorder treatment center Janus of Santa Cruz, said that Janus’ facility has only 40 beds. Those can fill up fast.

“The thing we need most is more space,” she said, adding that service providers have collaborated with each other effectively to get people to the right places. “All of the service providers here today are working really hard to get people in and help them get better.”

“There’s a high demand for care and beds are limited whether it’s through Janus or Encompass or New Life,” said Watsonville Health Center mental health case manager Andres Galvan. “But it’s our job to meet you where you’re at and we’re not going to deny services to anybody.”

Galvan agreed that coordination between service providers has gotten better, and organizations are easily able to contact each other and refer clients to the right place for them. He added that the county has also established a contract with The Camp Recovery Center — a drug and alcohol treatment facility with locations in Scotts Valley and San Jose — so that it will accept Medi-Cal for youth. The Camp typically takes only private insurance.

“That’s huge, because it’s hard for Santa Cruz County youth,” said Galvan. “You have outpatient services, but not much as far as residential.”

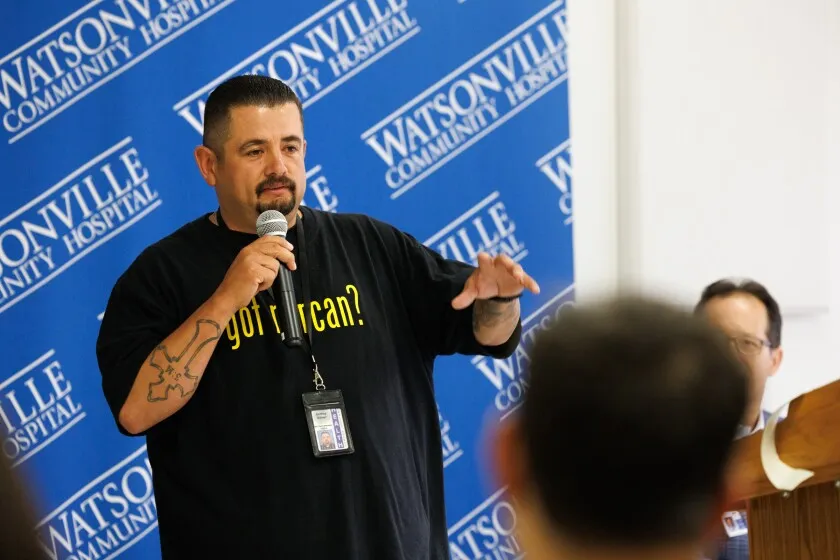

Andres Galvan speaks at Thursday’s event. Credit: Kevin Painchaud / Lookout Santa Cruz

“We don’t have any residential programs for youth with substance use disorder,” said Rita Hewitt, the program manager for local substance-use safety coalition SafeRx, noting that the crisis is hitting the youth much harder than before. “We haven’t had youth experiencing these problems until more recently, and it’s just catching up to us.”

Hewitt said she thinks that the tide could be turning, though. She recalls having difficulty getting in touch and coordinating with the County Office of Education in years past. Santa Cruz County has 10 different school districts that make independent decisions on things like Narcan use, and there was no Narcan policy in place until last June. On Thursday, the Office of Education had its own stand with free Narcan at the resource fair. “I’ve seen a huge shift in a desire to really destigmatize the issue and focus on saving lives,” Hewitt said.

However, service providers universally agreed that stigma remains the driving force behind the persisting — and worsening — opioid crisis. Hewitt said strong stigma lingers around using medications to treat opioid addiction, such as suboxone. That leads to people feeling shame or embarrassment when considering seeking help and can perpetuate a fear of seeking treatment.

Narcan at the Santa Cruz Office of Education’s table at Thursday’s event. Credit: Kevin Painchaud / Lookout Santa Cruz

“People can be stigmatized anywhere they go,” said Morrison. “We say that it’s 2023 and everyone’s accepted, but people still face it every day. If it’s not external, it’s internal.”

Some might get lost in a hopeless mindset, too. Galvan, who has been clean for nearly 20 years, said that when addiction, mental illness and homelessness compound, people can feel defeated and resigned to their situation.

“People still see it as a decision, and that users can stop if they want to, but that’s not the case,” he said. “We try to explain to those struggling that help is out there, and that it doesn’t have to stay this way.

“That’s a difficult task, and it’s easier said than done, but I think just conveying that message that there is hope, there is help, is huge.”

Aiden Fuller understands that message better than anyone, and summed it up for the crowd succinctly: “You know, if you fall, you just have to get back up.”

(Original Source: https://lookout.co/opioid-crisis-fentanyl-families-survivors-workers-share-personal-stories-of-opioid-struggles-crisis-epidemic-proportions/)